What Is the Time Period That a Chicken Takes to Lay Eggs Again

| Chicken | |

|---|---|

| |

| A rooster (left) and hen (right) perching on a roost | |

| Conservation status | |

| Domesticated | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Galliformes |

| Family unit: | Phasianidae |

| Genus: | Gallus |

| Species: | G. domesticus |

| Binomial name | |

| Gallus domesticus (Linnaeus, 1758) | |

| |

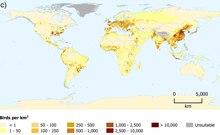

| Chicken distribution | |

The craven (Gallus domesticus) is a domesticated subspecies of the red junglefowl, with attributes of wild species such every bit grey and ceylon junglefowl[1] that are originally from Southeastern Asia. Rooster or cock is a term for an adult male bird, and a younger male may be called a cockerel. A male person that has been castrated is a capon. An adult female bird is called a hen and a sexually immature female is called a pullet.

Originally raised for cockfighting or for special ceremonies, chickens were not kept for food until the Hellenistic period (4th–2nd centuries BC).[ii] [3] Humans at present keep chickens primarily as a source of food (consuming both their meat and eggs) and equally pets.

Chickens are i of the well-nigh common and widespread domestic animals, with a total population of 23.vii billion as of 2018[update],[4] up from more than 19 billion in 2011.[5] There are more than chickens in the world than any other bird.[5] There are numerous cultural references to chickens – in myth, folklore and religion, and in linguistic communication and literature.

Genetic studies have pointed to multiple maternal origins in Southward Asia, Southeast Asia, and Eastern asia,[6] but the clade institute in the Americas, Europe, the Center Due east and Africa originated from the Indian subcontinent. From ancient India, the chicken spread to Lydia in western asia Small, and to Greece by the 5th century BC.[7] Fowl have been known in Egypt since the mid-15th century BC, with the "bird that gives birth every day" having come from the land between Syrian arab republic and Shinar, Babylonia, according to the annals of Thutmose III.[8] [nine] [ten]

Terminology

An adult male is a called a 'erect' or 'rooster' (in the Us) and an developed female is called a 'hen'.[eleven] [12]

Other terms are:

- 'Biddy': a newly hatched chicken[13] [fourteen]

- 'Capon': a castrated or neutered male person craven[a]

- 'Chick': a young chicken[15]

- 'Chook' : a chicken (Australia/New Zealand, informal)[16]

- 'Cockerel': a young male chicken less than a year erstwhile[17]

- 'Dunghill fowl': a chicken with mixed parentage from different domestic varieties.[18]

- 'Pullet': a young female chicken less than a yr old.[xix] In the poultry industry, a pullet is a sexually immature chicken less than 22 weeks of age.[20]

- 'Yardbird': a chicken (southern United States, dialectal)[21]

'Chicken' was originally a term only for an immature, or at least immature, bird.[ when? ] Nonetheless, thank you to its usage on restaurant menus, it has now become the almost common term for the subspecies in full general, especially in American English language. In older sources, 'chicken' every bit a species were typically referred to as 'common fowl' or 'domestic fowl'.[22]

'Chicken' may besides mean a 'chick' .[23]

Etymology

| | This section needs expansion with: the origin of the term 'chicken' in full general. You can help past adding to it. (June 2021) |

According to Merriam-Webster, the term 'rooster' (i.e. a roosting bird) originated in the mid- or belatedly 18th century as a euphemism to avoid the sexual connotation of the original English 'erect',[24] [25] [26] and is widely used throughout Northward America. 'Roosting' is the action of perching aloft to sleep at dark.[27]

Full general biological science and habitat

In most breeds the adult rooster tin be distinguished from the hen by his larger comb.

Chickens are omnivores.[28] In the wild, they oft scratch at the soil to search for seeds, insects, and fifty-fifty animals equally large every bit lizards, pocket-size snakes,[29] or sometimes young mice.[30]

The average chicken may live for v–ten years, depending on the breed.[31] The world'southward oldest known craven lived 16 years according to Guinness World Records.[32]

Diagram of a chicken skull.

Eggs from unlike breeds

Roosters tin usually be differentiated from hens by their striking plumage of long flowing tails and shiny, pointed feathers on their necks ('hackles') and backs ('saddle'), which are typically of brighter, bolder colours than those of females of the aforementioned brood. However, in some breeds, such as the Sebright chicken, the rooster has just slightly pointed neck feathers, the same colour as the hen's. The identification tin exist made by looking at the comb, or somewhen from the development of spurs on the male's legs (in a few breeds and in certain hybrids, the male and female chicks may be differentiated by color). Developed chickens have a fleshy crest on their heads called a comb, or cockscomb, and hanging flaps of peel either side under their beaks called wattles. Collectively, these and other fleshy protuberances on the head and throat are chosen caruncles. Both the adult male and female have wattles and combs, but in nearly breeds these are more prominent in males. A 'muff' or 'beard' is a mutation found in several chicken breeds which causes extra feathering under the craven's face up, giving the advent of a beard.[33]

Domestic chickens are non capable of long-distance flight, although lighter chickens are by and large capable of flying for brusque distances, such as over fences or into trees (where they would naturally roost). Chickens may occasionally fly briefly to explore their surroundings, simply generally exercise and then only to abscond perceived danger.

Behavior

Hen with chicks, Portugal

Chickens are gregarious birds and live together in flocks. They have a communal approach to the incubation of eggs and raising of young. Individual chickens in a flock will boss others, establishing a 'pecking order', with dominant individuals having priority for food access and nesting locations. Removing hens or roosters from a flock causes a temporary disruption to this social lodge until a new pecking gild is established. Adding hens, peculiarly younger birds, to an existing flock can atomic number 82 to fighting and injury.[34]

When a rooster finds food, he may phone call other chickens to consume get-go. He does this by clucking in a loftier pitch as well as picking up and dropping the food. This behaviour may also be observed in mother hens to call their chicks and encourage them to eat.

A rooster's crowing is a loud and sometimes shrill call and sends a territorial point to other roosters.[35] Notwithstanding, roosters may also crow in response to sudden disturbances within their surroundings. Hens cluck loudly subsequently laying an egg, and also to call their chicks. Chickens besides requite different warning calls when they sense a predator approaching from the air or on the ground.[36]

Crowing

Roosters almost always first exultation earlier four months of age. Although it is possible for a hen to crow as well, crowing (together with hackles development) is i of the clearest signs of beingness a rooster.[37]

Rooster crowing contests

Rooster crowing contests, also known as crowing contests, are a traditional sport in several countries, such as Frg, the netherlands, Belgium,[38] the United States, Indonesia and Japan. The oldest contests are held with longcrowers. Depending on the breed, either the duration of the exultation or the times the rooster crows within a sure time is measured.

Courtship

To initiate courting, some roosters may dance in a circumvolve effectually or near a hen (a 'circumvolve trip the light fantastic'), often lowering the wing which is closest to the hen.[39] The dance triggers a response in the hen[39] and when she responds to his 'phone call', the rooster may mount the hen and continue with the mating.

More specifically, mating typically involves the post-obit sequence:

- Male approaching the hen

- Male person pre-copulatory waltzing

- Male person waltzing

- Female crouching (receptive posture) or stepping aside or running away (if unwilling to copulate)

- Male mounting

- Male treading with both anxiety on hen's dorsum

- Male tail bending (following successful copulation)[40]

Nesting and laying behaviour

Chicken eggs vary in colour depending on the breed, and sometimes, the hen, typically ranging from bright white to shades of brown and even blue, green, light pinkish and recently reported majestic (found in Due south Asia) (Araucana varieties).

Chicks before their first outing

Hens will ofttimes try to lay in nests that already contain eggs and accept been known to movement eggs from neighbouring nests into their ain. The result of this behaviour is that a flock will use only a few preferred locations, rather than having a different nest for every bird. Hens will ofttimes express a preference to lay in the same location. It is not unknown for 2 (or more) hens to try to share the same nest at the same time. If the nest is small, or one of the hens is particularly determined, this may effect in chickens trying to lay on top of each other. At that place is evidence that private hens prefer to be either solitary or gregarious nesters.[41]

A chick sitting in a person's mitt

Broodiness

Under natural weather condition, virtually birds lay only until a clutch is complete, and they volition then incubate all the eggs. Hens are then said to "go broody". The broody hen volition stop laying and instead will focus on the incubation of the eggs (a total clutch is usually about 12 eggs). She will sit down or 'set' on the nest, fluffing up or pecking in defense force if disturbed or removed. The hen volition rarely leave the nest to eat, drink, or dust-bathe.[42] While brooding, the hen maintains the nest at a abiding temperature and humidity, likewise as turning the eggs regularly during the first part of the incubation. To stimulate broodiness, owners may place several bogus eggs in the nest. To discourage information technology, they may place the hen in an elevated cage with an open wire floor.

Skull of a 3-week-onetime chicken. Here the opisthotic bone appears in the occipital region, as in the developed Chelonian. bo = Basi-occipital, bt = Basi-temporal, eo = Opisthotic, f = Frontal, fm = Foramen magnum, fo = Fontanella, oc = Occipital condyle, op = Opisthotic, p = Parietal, pf = Post-frontal, sc = Sinus canal in supra-occipital, so = Supra-occpital, sq = Squamosal, 8 = Exit of vagus nervus.

Breeds artificially developed for egg production rarely go broody, and those that do often terminate office-way through the incubation. However, other breeds, such as the Cochin, Cornish and Silkie, do regularly get broody, and make first-class mothers, not just for chicken eggs but also for those of other species — even those with much smaller or larger eggs and different incubation periods, such every bit quail, pheasants, ducks, turkeys, or geese.

Hatching and early life

Fertile craven eggs hatch at the end of the incubation period, about 21 days.[39] Development of the chick starts simply when incubation begins, so all chicks hatch within a twenty-four hours or ii of each other, despite perhaps existence laid over a flow of two weeks or so. Before hatching, the hen can hear the chicks peeping within the eggs, and volition gently cluck to stimulate them to suspension out of their shells. The chick begins by 'pipping'; pecking a breathing pigsty with its egg tooth towards the edgeless stop of the egg, usually on the upper side. The chick then rests for some hours, arresting the remaining egg yolk and withdrawing the blood supply from the membrane beneath the vanquish (used earlier for breathing through the shell). The chick and so enlarges the pigsty, gradually turning round every bit it goes, and somewhen severing the edgeless end of the vanquish completely to make a lid. The chick crawls out of the remaining shell, and the wet down dries out in the warmth of the nest.

Hens usually remain on the nest for about two days afterward the commencement chick hatches, and during this time the newly hatched chicks feed by absorbing the internal yolk sac. Some breeds sometimes start eating cracked eggs, which can become habitual.[43] Hens fiercely guard their chicks, and brood them when necessary to keep them warm, at first often returning to the nest at night. She leads them to nutrient and water and will call them toward edible items, merely seldom feeds them direct. She continues to care for them until they are several weeks erstwhile.

Defensive behaviour

Chickens may occasionally gang up on a weak or inexperienced predator. At least one apparent report exists of a young fox killed by hens.[44] [45] [46] A group of hens accept been recorded in attacking a militarist that had entered their coop.[47]

If a craven is threatened past predators, stress, or is sick, there is a chance that they volition puff up their feathers.[42]

Reproduction

Sperm transfer occurs by cloacal contact between the male person and female, in a maneuver known equally the 'cloacal kiss'.[48] As with birds in full general, reproduction is controlled by a neuroendocrine organisation, the Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone-I neurons in the hypothalamus. Locally to the reproductive system itself, reproductive hormones such every bit estrogen, progesterone, gonadotropins (luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone) initiate and maintain sexual maturation changes. Over time there is reproductive decline, thought to be due to GnRH-I-North refuse. Because there is meaning inter-individual variability in egg-producing elapsing, information technology is believed to exist possible to breed for further extended useful lifetime in egg-layers.[49]

Embryology

(Video) Earliest gestation stages and claret apportionment of a chicken embryo

Chicken embryos have long been used every bit model systems to study developing embryos. Large numbers of embryos can be provided past commercial chicken farmers who sell fertilized eggs which can be easily opened and used to observe the developing embryo. Equally important, embryologists can comport out experiments on such embryos, close the egg again and study the effect afterwards. For instance, many important discoveries in the surface area of limb development accept been fabricated using chicken embryos, such as the discovery of the apical ectodermal ridge (AER) and the zone of polarizing activity (ZPA) by John Due west. Saunders.[50]

In 2006, scientists researching the ancestry of birds "turned on" a chicken recessive factor, talpid2, and constitute that the embryo jaws initiated formation of teeth, like those institute in ancient bird fossils. John Fallon, the overseer of the project, stated that chickens have "...retained the ability to make teeth, under certain weather... ."[51]

The G. gallus genome has 39 pairs of chromosomes, whereas the man genome contains 23 pairs

Genetics and genomics

Given its eminent role in farming, meat production, but as well enquiry, the house chicken was the start bird genome to exist sequenced.[52] At i.21 Gb, the chicken genome is considerably smaller than other vertebrate genomes, such as the homo genome (3 Gb). The final factor set contained 26,640 genes (including noncoding genes and pseudogenes), with a total of 19,119 protein-coding genes in annotation release 103 (2017), a similar number of protein-coding genes equally in the man genome.[53]

Physiology

Populations of chickens from high altitude regions like Tibet have special physiological adaptations that result in a higher hatching rate in low oxygen environments. When eggs are placed in a hypoxic environment, chicken embryos from these populations express much more hemoglobin than embryos from other craven populations. This hemoglobin also has a greater affinity for oxygen, allowing hemoglobin to bind to oxygen more readily.[54] [55]

Pinopsins were originally discovered in the chicken pineal gland.[56]

Immunology

Although all avians appear to have lost TLR9, bogus immunity against bacterial pathogens has been induced in neonatal chicks by Taghavi et al 2008 using tailored oligodeoxynucleotides.[57]

Breeding

Origins

Galliformes, the order of bird that chickens vest to, is directly linked to the survival of birds when all other dinosaurs went extinct. H2o or basis-domicile fowl, like to modern partridges, survived the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event that killed all tree-domicile birds and dinosaurs.[58] Some of these evolved into the modern galliformes, of which domesticated chickens are a main model. They are descended primarily from the red junglefowl (Gallus gallus) and are scientifically classified as the same species.[59] As such, domesticated chickens can and practise freely interbreed with populations of carmine junglefowl.[59] Subsequent hybridization of the domestic craven with greyness junglefowl, Sri Lankan junglefowl and dark-green junglefowl occurred;[threescore] a gene for yellow skin, for example, was incorporated into domestic birds through hybridization with the grey junglefowl (G. sonneratii).[61] In a study published in 2020, it was found that chickens shared between 71% - 79% of their genome with red junglefowl, with the menstruation of domestication dated to 8,000 years agone.[60]

Red junglefowl hen in India

The traditional view is that chickens were beginning domesticated for cockfighting in Asia, Africa, and Europe.[2] In the concluding decade, there have been a number of genetic studies to clarify the origins. According to i early on study, a single domestication event of the red junglefowl in what now is the state of Thailand gave rise to the modern chicken with minor transitions separating the modern breeds.[62] The carmine junglefowl, known as the bamboo fowl in many Southeast Asian languages, is well adapted to have advantage of the vast quantities of seed produced during the terminate of the multi-decade bamboo seeding cycle, to boost its own reproduction.[63] In domesticating the craven, humans took advantage of this predisposition for prolific reproduction of the cherry junglefowl when exposed to large amounts of food.[64]

Exactly when and where the chicken was domesticated remains a controversial consequence. Genomic studies guess that the chicken was domesticated viii,000 years ago[threescore] in Southeast Asia and spread to Cathay and India 2000–3000 years subsequently. Archaeological testify supports domestic chickens in Southeast Asia well before 6000 BC, People's republic of china by 6000 BC and India by 2000 BC.[60] [65] [66] A landmark 2020 Nature study that fully sequenced 863 chickens beyond the earth suggests that all domestic chickens originate from a single domestication event of red junglefowl whose present-day distribution is predominantly in southwestern China, northern Thailand and Myanmar. These domesticated chickens spread across Southeast and Southern asia where they interbred with local wild species of junglefowl, forming genetically and geographically distinct groups. Analysis of the about pop commercial breed shows that the White Leghorn brood possesses a mosaic of divergent ancestries inherited from subspecies of reddish junglefowl.[67] [68] [69]

Eye Eastern craven remains go back to a petty before than 2000 BC in Syria; chickens went southward only in the 1st millennium BC. They reached Arab republic of egypt for purposes of cockfighting about 1400 BC, and became widely bred merely in Ptolemaic Egypt (about 300 BC).[70] Phoenicians spread chickens along the Mediterranean coasts as far every bit Iberia. During the Hellenistic period (4th–2nd centuries BC), in the Southern Levant, chickens began to be widely domesticated for nutrient.[iii] This change occurred at least 100 years before domestication of chickens spread to Europe.

Chickens reached Europe circa 800 BC.[71] Breeding increased under the Roman Empire, and was reduced in the Eye Ages.[lxx] Genetic sequencing of chicken basic from archaeological sites in Europe revealed that in the Loftier Centre Ages chickens became less ambitious and began to lay eggs earlier in the breeding season.[72]

Iii possible routes of introduction into Africa around the early first millennium AD could have been through the Egyptian Nile Valley, the E Africa Roman-Greek or Indian trade, or from Carthage and the Berbers, beyond the Sahara. The primeval known remains are from Mali, Nubia, Due east Coast, and South Africa and date back to the centre of the starting time millennium AD.[70]

Domestic chicken in the Americas before Western contact is however an ongoing word, simply blue-egged chickens, establish but in the Americas and Asia, suggest an Asian origin for early American chickens.[70]

A lack of data from Thailand, Russian federation, the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa makes information technology hard to lay out a articulate map of the spread of chickens in these areas; better description and genetic assay of local breeds threatened by extinction may also assistance with research into this surface area.[70]

South America

An unusual variety of chicken that has its origins in South America is the Araucana, bred in southern Chile by the Mapuche people. Araucanas lay blue-dark-green eggs. Additionally, some Araucanas are tailless, and some accept tufts of feathers around their ears. It has long been suggested that they pre-date the arrival of European chickens brought past the Castilian and are evidence of pre-Columbian trans-Pacific contacts between Asian or Pacific Oceanic peoples, particularly the Polynesians, and S America. In 2007, an international team of researchers reported the results of their analysis of chicken bones establish on the Arauco Peninsula in south-central Chile. Radiocarbon dating suggested that the chickens were pre-Columbian, and Deoxyribonucleic acid analysis showed that they were related to prehistoric populations of chickens in Polynesia.[73] These results appeared to confirm that the chickens came from Polynesia and that there were transpacific contacts between Polynesia and South America before Columbus'southward inflow in the Americas.[74] [75]

Notwithstanding, a afterwards report looking at the same specimens ended:

A published, obviously pre-Columbian, Chilean specimen and six pre-European Polynesian specimens as well cluster with the same European/Indian subcontinental/Southeast Asian sequences, providing no support for a Polynesian introduction of chickens to South America. In contrast, sequences from ii archaeological sites on Easter Isle group with an uncommon haplogroup from Indonesia, Nippon, and People's republic of china and may correspond a genetic signature of an early Polynesian dispersal. Modeling of the potential marine carbon contribution to the Chilean archaeological specimen casts further doubt on claims for pre-Columbian chickens, and definitive proof will crave further analyses of ancient DNA sequences and radiocarbon and stable isotope data from archaeological excavations within both Chile and Polynesia.[76]

The contend for and confronting a Polynesian origin for South American chickens connected with this 2014 paper and subsequent responses in PNAS.[77]

Use past humans

Farming

A former battery hen, five days after release. Notation the pale comb – the rummage may be an indicator of health or vigor.[78]

More than than 50 billion chickens are reared annually as a source of meat and eggs.[79] In the United States lonely, more than 8 billion chickens are slaughtered each year for meat,[80] and more than than 300 million chickens are reared for egg product.[81]

The vast majority of poultry are raised in manufacturing plant farms. According to the Worldwatch Institute, 74 pct of the world's poultry meat and 68 percent of eggs are produced this fashion.[82] An alternative to intensive poultry farming is gratuitous-range farming.

Friction between these two main methods has led to long-term issues of ethical consumerism. Opponents of intensive farming argue that information technology harms the environment, creates human health risks and is inhumane.[83] Advocates of intensive farming say that their highly efficient systems save land and food resources owing to increased productivity, and that the animals are looked after in state-of-the-fine art environmentally controlled facilities.[84]

Reared for meat

A commercial chicken firm with open sides raising broiler pullets for meat

Chickens farmed for meat are chosen broilers. Chickens will naturally live for six or more than years, but broiler breeds typically have less than six weeks to reach slaughter size.[85] A gratuitous range or organic broiler will usually be slaughtered at nigh fourteen weeks of age.

Reared for eggs

Chickens farmed primarily for eggs are called layer hens. In total, the U.k. alone consumes more than 34 million eggs per day.[86] Some hen breeds tin produce over 300 eggs per year, with "the highest authenticated rate of egg laying existence 371 eggs in 364 days".[87] After 12 months of laying, the commercial hen'due south egg-laying ability starts to decline to the point where the flock is commercially unviable. Hens, particularly from battery muzzle systems, are sometimes infirm or take lost a significant corporeality of their feathers, and their life expectancy has been reduced from around vii years to less than 2 years.[88] In the UK and Europe, laying hens are and so slaughtered and used in candy foods or sold equally 'soup hens'.[88] In another countries, flocks are sometimes strength moulted, rather than being slaughtered, to re-invigorate egg-laying. This involves complete withdrawal of food (and sometimes water) for 7–fourteen days[89] or sufficiently long to cause a body weight loss of 25 to 35%,[90] or up to 28 days under experimental conditions.[91] This stimulates the hen to lose her feathers, simply also re-invigorates egg-production. Some flocks may exist forcefulness-moulted several times. In 2003, more than 75% of all flocks were moulted in the United states of america.[92]

Every bit pets

A 95-year-old woman from Havana, Cuba, with her pet rooster

Keeping chickens as pets became increasingly popular in the 2000s[93] amongst urban and suburban residents.[94] Many people obtain chickens for their egg production but frequently proper noun them and treat them every bit any other pet like cats or dogs. Chickens provide companionship and have private personalities. While many do not cuddle much, they will swallow from one'southward manus, jump onto ane's lap, respond to and follow their handlers, also equally show affection.[95] [96]

Chickens are social, inquisitive, intelligent[97] birds, and many find their behaviour entertaining.[98] Certain breeds, such as Silkies and many bantam varieties, are generally docile and are oft recommended as practiced pets around children with disabilities.[99] Many people feed chickens in part with kitchen food scraps.

Backyard heritage chickens eating kitchen food scraps.

Cockfighting

A cockfight is a contest held in a band chosen a cockpit between ii cocks known as gamecocks. This term, denoting a erect kept for game, sport, pastime or amusement, appears in 1646,[100] later on "cock of the game" used past George Wilson in the earliest known volume on the secular sport, The Commendation of Cocks and Cock Fighting of 1607. Gamecocks are not typical farm chickens. The cocks are especially bred and trained for increased stamina and strength. The comb and wattle are removed from a immature gamecock considering, if left intact, they would be a disadvantage during a match. This process is called dubbing. Sometimes the cocks are given drugs to increment their stamina or thicken their claret, which increases their chances of winning. Cockfighting is considered a traditional sporting effect by some, and an example of fauna cruelty by others and is therefore outlawed in most countries.[101] Normally wagers are made on the outcome of the friction match, with the survivor or final bird standing declared winner.

Chickens were originally used for cockfighting, a sport where two male person chickens (cocks) fight each other until ane dies or becomes badly injured. Cocks possess congenital aggression toward all other cocks to contest with females. Studies advise that cockfights take existed even up to the Indus Valley Culture every bit a pastime.[102] Today it is commonly associated with religious worship, pastime, and gambling in Asian and some South American countries. While not all fights are to the death, about use metal spurs as a weapon fastened above or below the chicken'due south own spur, which typically results in expiry in ane or both cocks. If chickens are in practice, owners place gloves on the spurs to forestall injuries. Cockfighting has been banned in most western countries and debated by animal rights activists for its brutality.

Bogus incubation

Incubation tin occur artificially in machines that provide the correct, controlled environment for the developing chick.[103] [104] The average incubation period for chickens is 21 days but the elapsing depends on the temperature and humidity in the incubator. Temperature regulation is the almost disquisitional cistron for a successful hatch. Variations of more than 1 °C (1.8 °F) from the optimum temperature of 37.5 °C (99.five °F) will reduce hatch rates. Humidity is also important because the rate at which eggs lose h2o past evaporation depends on the ambient relative humidity. Evaporation can be assessed past candling, to view the size of the air sac, or by measuring weight loss. Relative humidity should be increased to around 70% in the last three days of incubation to go along the membrane around the hatching chick from drying out after the chick cracks the shell. Lower humidity is usual in the first eighteen days to ensure adequate evaporation. The position of the eggs in the incubator can also influence hatch rates. For best results, eggs should be placed with the pointed ends down and turned regularly (at least iii times per day) until one to three days before hatching. If the eggs aren't turned, the embryo within may stick to the vanquish and may hatch with physical defects. Adequate ventilation is necessary to provide the embryo with oxygen. Older eggs require increased ventilation.

Many commercial incubators are industrial-sized with shelves holding tens of thousands of eggs at a time, with rotation of the eggs a fully automated process. Home incubators are boxes holding from 6 to 75 eggs; they are usually electrically powered, but in the by some were heated with an oil or paraffin lamp.

Diseases and ailments

Chickens are susceptible to several parasites, including lice, mites, ticks, fleas, and abdominal worms, as well as other diseases. Despite the name, they are not affected by chickenpox, which is generally restricted to humans.[105]

Chickens tin can carry and transmit salmonella in their dander and carrion. In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advise against bringing them indoors or letting small children handle them.[106] [107]

Some of the diseases that tin touch on chickens are shown below:

| Proper name | Common name | Cause |

|---|---|---|

| Aspergillosis | Aspergillus fungi | |

| Avian influenza | bird flu | virus |

| Histomoniasis | blackhead disease | Histomonas meleagridis |

| Botulism | paralysis | Clostridium botulinum toxin |

| Cage layer fatigue | mineral deficiency, lack of physical exercise | |

| Campylobacteriosis | tissue injury in the gut | |

| Coccidiosis | Coccidia | |

| Colds | virus | |

| Crop bound Archived 2010-10-26 at the Wayback Machine | improper feeding | |

| Dermanyssus gallinae | carmine mite | parasite |

| Egg binding | oversized egg | |

| Erysipelas | Streptococcus bacteria | |

| Fat liver hemorrhagic syndrome | high-energy food | |

| Fowl cholera | Pasteurella multocida | |

| Fowlpox | Fowlpox virus | |

| Fowl typhoid | bacteria | |

| Avian infectious laryngotracheitis | LT | Gallid alphaherpesvirus 1 |

| Gapeworm | Syngamus trachea | worms |

| Infectious bronchitis | Infectious bronchitis virus | |

| Infectious bursal disease | Gumboro | infectious bursal disease virus |

| Infectious coryza in chickens | Avibacterium paragallinarum | |

| Lymphoid leukosis | Avian sarcoma leukosis virus | |

| Marek's disease | Gallid alphaherpesvirus ii | |

| Moniliasis | yeast infection or thrush | Candida fungi |

| Mycoplasma | bacteria | |

| Newcastle disease | Avian avulavirus ane | |

| Necrotic enteritis Archived 2010-12-16 at the Wayback Auto | bacteria | |

| Omphalitis | Mushy chick disease[108] | leaner |

| Peritonitis[109] | infection in abdomen from egg yolk | |

| Psittacosis | Chlamydia psittaci | |

| Pullorum | Salmonella | bacteria |

| Scaly leg | Knemidokoptes mutans | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | cancer | |

| Tibial dyschondroplasia | speed growing | |

| Toxoplasmosis | Toxoplasma gondii | |

| Ulcerative enteritis | bacteria | |

| Ulcerative pododermatitis | bumblefoot | bacteria |

History

An early domestication of chickens in Southeast Asia is probable, since the discussion for domestic craven (*manuk) is role of the reconstructed Proto-Austronesian linguistic communication . Chickens, together with dogs and pigs, were the domestic animals of the Lapita civilisation,[110] the start Neolithic culture of Oceania.[111]

The outset pictures of chickens in Europe are establish on Corinthian pottery of the 7th century BC.[112] [113]

Chickens were spread by Polynesian seafarers and reached Easter Island in the 12th century AD, where they were the but domestic fauna, with the possible exception of the Polynesian rat (Rattus exulans). They were housed in extremely solid chicken coops built from rock, which was start reported as such to Linton Palmer in 1868, who likewise "expressed his doubts nearly this".[114]

In culture

Abraxas seen with a chicken's head

The mythological basilisk or cockatrice is depicted as a reptile-like beast with the upper trunk of a rooster.[115] [116] Abraxas, a figure in Gnosticism, is portrayed in a similar fashion too.[117]

Gallery

-

Rooster in the coat of arms of Laitila

-

-

-

A grouping of chicks

See likewise

- Abnormal behaviour of birds in captivity

- Battery Hen Welfare Trust, a Britain clemency for laying hens

- Chicken as food

- Craven eyeglasses

- Chicken fat

- Chicken hypnotism

- Chicken or the egg

- Chicken manure

- Chook raffle – a blazon of raffle where the prize is a chicken.

- Early on feeding

- Feral chicken

- Gamebird hybrids – hybrids betwixt chickens, peafowl, guineafowl and pheasants

- Henopause

- Hen and chicks, a type of establish

- List of chicken breeds

- Poularde

- Condom chicken

- Sex modify in chickens

- Symbolic chickens

- "Tastes similar craven"

- Unihemispheric slow-moving ridge slumber

- Urban chicken keeping

- "Why did the chicken cantankerous the route?"

Roosters

- Chicken laugh

- Cock egg

- Red Junglefowl

- Rooster Flag (disambiguation)

- Rooster of Barcelos

Explanatory notes

- ^ The surgical and chemical castration of chickens is at present illegal in some parts of the world

References

- ^

- Lawal, Raman Akinyanju; Martin, Simon H.; Vanmechelen, Koen; Vereijken, Addie; Silva, Pradeepa; Al-Atiyat, Raed Mahmoud; Aljumaah, Riyadh Salah; Mwacharo, Joram Thou.; Wu, Dong-Dong; Zhang, Ya-Ping; Hocking, Paul Thou.; Smith, Jacqueline; Wragg, David; Hanotte, Olivier (2020-02-12). "The wild species genome ancestry of domestic chickens". BMC Biological science. BioMed Central. 18 (1): 13. doi:10.1186/s12915-020-0738-1. ISSN 1741-7007. PMC7014787. PMID 32050971. S2CID 211081254.

- Tiley, George P.; Poelstra, Jelmer West.; dos Reis, Mario; Yang, Ziheng; Yoder, Anne D. (2020). "Molecular Clocks without Rocks: New Solutions for Old Issues". Trends in Genetics. Cell Press. 36 (11): 845–856. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2020.06.002. ISSN 0168-9525. PMID 32709458. S2CID 220747034.

- Tregaskes, Clive A.; Kaufman, Jim (2021). "Chickens as a elementary arrangement for scientific discovery: The example of the MHC". Molecular Immunology. Elsevier. 135: 12–20. doi:10.1016/j.molimm.2021.03.019. ISSN 0161-5890. PMC7611830. PMID 33845329. S2CID 233223219. EuroPMC manus. 136199.

- Lawal, R. A.; Hanotte, O. (2021-05-31). "Domestic chicken diverseness: Origin, distribution, and adaptation". Animal Genetics. International Foundation for Animal Genetics (Wiley). 52 (4): 385–394. doi:ten.1111/historic period.13091. ISSN 0268-9146. PMID 34060099. S2CID 235268576.

- Siegel, Paul B.; Honaker, Christa F.; Scanes, Colin G. (2022). "Domestication of poultry". Sturkie's Avian Physiology. Elsevier. pp. 109–120. doi:ten.1016/b978-0-12-819770-seven.00026-8. ISBN978-0-12-819770-7. S2CID 244084328.

- Eda, Masaki (2021-05-01). "Origin of the domestic craven from modern biological and zooarchaeological approaches". Creature Frontiers. American Club of Animal Science (OUP). 11 (3): 52–61. doi:10.1093/af/vfab016. ISSN 2160-6056. PMC8214436. PMID 34158989. S2CID 235593797.

- van Grouw, Hein; Dekkers, Wim (2020-09-21). "Temminck's Gallus giganteus; a gigantic obstacle to Darwin'due south theory of domesticated fowl origin?". Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Social club. British Ornithologists' Club. 140 (3). doi:10.25226/bboc.v140i3.2020.a5. ISSN 0007-1595. S2CID 221823963.

- ^ a b "The Ancient City Where People Decided to Eat Chickens". NPR. Archived from the original on May xvi, 2018. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- ^ a b Perry-Gal, Lee; Erlich, Adi; Gilboa, Ayelet; Bar-Oz, Guy (11 August 2015). "Earliest economical exploitation of craven outside East asia: Evidence from the Hellenistic Southern Levant". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112 (32): 9849–9854. Bibcode:2015PNAS..112.9849P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1504236112. PMC4538678. PMID 26195775.

- ^ "Number of chickens worldwide from 1990 to 2018". Statista . Retrieved February 23, 2020.

- ^ a b UN's Food and Agriculture Organisation (July 2011). "Global Livestock Counts". The Economist. Archived from the original on July 15, 2016. Retrieved July thirteen, 2017.

- ^ Xiang, Hai; Gao, Jianqiang; Yu, Baoquan; Zhou, Hui; Cai, Dawei; Zhang, Youwen; Chen, Xiaoyong; Wang, Xi; Hofreiter, Michael; Zhao, Xingbo (9 December 2014). "Early Holocene chicken domestication in northern Mainland china". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (49): 17564–17569. Bibcode:2014PNAS..11117564X. doi:ten.1073/pnas.1411882111. PMC4267363. PMID 25422439.

- ^ Maguelonne Toussaint-Samat, (Anthea Bell, translator) The History of Food, Ch. 11 "The History of Poultry", revised ed. 2009, p. 306.

- ^ Carter, Howard (April 1923). "An Ostracon Depicting a Blood-red Jungle-Fowl (The Earliest Known Drawing of the Domestic Cock)". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 9 (ane/2): 1–4. doi:10.2307/3853489. JSTOR 3853489.

- ^ Pritchard, Earl H. "The Asiatic Campaigns of Thutmose III". Ancient Near East Texts related to the Old Testament. p. 240.

- ^ Roehrig, Catharine H.; Dreyfus, Renée; Keller, Cathleen A. (2005). Hatshepsut: From Queen to Pharaoh. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 268. ISBN978-1-58839-173-5 . Retrieved Nov 26, 2015.

- ^ "Cock". Cambridge Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2015-09-07. Retrieved four March 2021.

- ^ "Hen". Cambridge Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2015-09-07. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ^ "Definition of biddy | Dictionary.com". www.lexicon.com.

- ^ "Biddy definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary". www.collinsdictionary.com.

- ^ "Chick". Cambridge Lexicon. Archived from the original on 2015-09-07.

- ^ "Chook". Cambridge Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2015-09-07. Retrieved iv March 2021.

- ^ Cockerel. Dictionary.reference.com. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved Baronial 29, 2010.

- ^ Richardson, H. D. (1847). Domestic fowl: their natural history, breeding, rearing, and general management . Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ Pullet. Dictionary.reference.com. Archived from the original on Nov 9, 2010. Retrieved Baronial 29, 2010.

- ^ "Overview of the Poultry Industry" (PDF). Overview of the Poultry Industry. Missouri Department of Elementary and Secondary Pedagogy. p. 8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-10-23.

- ^ Berhardt, Clyde Eastward. B. (1986). I Think: Fourscore Years of Black Entertainment, Big Bands. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 153. ISBN978-0-8122-8018-0. OCLC 12805260.

- ^ Dohner, Janet Vorwald (January 1, 2001). The Encyclopedia of Historic and Endangered Livestock and Poultry Breeds. Yale University Press. ISBN978-0300138139. Archived from the original on June 28, 2016. Retrieved Feb 14, 2016.

- ^ "Chicken". Merriam Webster Lexicon. Archived from the original on 2008-08-21. Retrieved iv March 2021.

- ^ "Definition of ROOSTER". www.merriam-webster.com.

- ^ Hugh Rawson "Why Exercise We Say...? Rooster", American Heritage, Aug./Sept. 2006.

- ^ Online Etymology Dictionary Entry for rooster (n.), May 2019

- ^ "Definition of ROOST". Collins English Dictionary. Retrieved sixteen October 2021.

- ^ "Info on Chicken Care". Ideas-iv-pets.co.united kingdom. 2003. Archived from the original on June 25, 2015. Retrieved August 13, 2008.

- ^ D Lines (July 27, 2013). "Chicken Kills Rattlesnake". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2021-12-11. Retrieved March 13, 2019.

- ^ Gerard P.Worrell AKA "Farmer Jerry". "Frequently asked questions well-nigh chickens & eggs". Gworrell.freeyellow.com. Archived from the original on September 16, 2008. Retrieved August thirteen, 2008.

- ^ "The Poultry Guide – A to Z and FAQs". Ruleworks.co.great britain. Archived from the original on Nov 28, 2010. Retrieved Baronial 29, 2010.

- ^ Smith, Jamon (August 6, 2006). "World'southward oldest chicken starred in magic shows, was on 'Tonight Show'". Tuscaloosa News. Alabama, USA. Archived from the original on February xx, 2019. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- ^ Ying Guo, Xiaorong Gu, Zheya Sheng, Yanqiang Wang, Chenglong Luo, Ranran Liu, Hao Qu, Dingming Shu, Jie Wen, Richard P. M. A. Crooijmans, Örjan Carlborg, Yiqiang Zhao, Xiaoxiang Hu, Ning Li (2016). A Complex Structural Variation on Chromosome 27 Leads to the Ectopic Expression of HOXB8 and the Muffs and Beard Phenotype in Chickens. PLoS Genetics. 12 (6): e1006071. doi:x.1371/journal.pgen.1006071.

- ^ "Introducing new hens to a flock " Musings from a Stonehead". Stonehead.wordpress.com. Archived from the original on Baronial 13, 2010. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- ^ "Summit cock: Roosters crow in pecking order". Archived from the original on January 15, 2018. Retrieved January 14, 2018.

- ^ Evans, Christopher S.; Evans, Linda; Marler, Peter (July 1993). "On the meaning of alarm calls: functional reference in an avian vocal system". Animal Behaviour. 46 (1): 23–38. doi:10.1006/anbe.1993.1158. S2CID53165305.

- ^ Read, Gina (five July 2008). "Sexing Chickens". Keeping Chickens Newsletter. keepingchickensnewsletter.com. Retrieved 5 July 2008.

- ^ Cock crowing contest recognised equally National Heritage in Belgium Stefaan De Groote, Het Nieuwsblad, 27. June 2011 (in Dutch). Accessed October 2015

- ^ a b c Grandin, Temple; Johnson, Catherine (2005). Animals in Translation . New York City: Scribner. pp. 69–71. ISBN978-0-7432-4769-6.

- ^ Cheng, Kimberly M.; Burns, Jeffrey T. (August 1988). "Authorization Relationship and Mating Behavior of Domestic Cocks: A Model to Report Mate-Guarding and Sperm Competition in Birds". The Condor. xc (iii): 697–704. doi:10.2307/1368360. JSTOR 1368360.

- ^ Sherwin, C.M.; Nicol, C.J. (1993). "Factors influencing flooring-laying by hens in modified cages". Applied Animal Behaviour Scientific discipline. 36 (ii–3): 211–222. doi:x.1016/0168-1591(93)90011-d.

- ^ a b "Why Do Chickens Puff up Their Feathers? I 4 Reasons Explained". 8 Baronial 2020. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- ^ Ali, A.; Cheng, K.One thousand. (1985). "Early egg production in genetically blind (rc/rc) chickens in comparison with sighted (Rc+/rc) controls". Poultry Scientific discipline. 64 (v): 789–794. doi:ten.3382/ps.0640789. PMID 4001066.

- ^ "Chickens squad upwards to 'peck fox to death'". The Independent. March thirteen, 2019. Archived from the original on March 15, 2019. Retrieved March 13, 2019.

- ^ "Chickens 'gang upward' to kill fob". Bbc.co.great britain. March xiii, 2019. Archived from the original on March 14, 2019. Retrieved March 13, 2019.

- ^ AFP (March 12, 2019). "Chickens 'teamed up to kill play tricks' at Brittany farming school". Theguardian.com. Archived from the original on March thirteen, 2019. Retrieved March 13, 2019.

- ^ "Check this out! This militarist thought he'd accept a craven dinner until he met our hens". Rustic Road Farm – via Facebook.

- ^ Briskie, J. V.; R. Montgomerie (1997). "Sexual Selection and the Intromittent Organ of Birds". Journal of Avian Biology. 28 (ane): 73–86. doi:x.2307/3677097. JSTOR 3677097.

- ^ Bain, Thousand. Grand.; Nys, Y.; Dunn, I.C. (2016-05-03). "Increasing persistency in lay and stabilising egg quality in longer laying cycles. What are the challenges?". British Poultry Science. Taylor & Francis. 57 (3): 330–338. doi:ten.1080/00071668.2016.1161727. ISSN 0007-1668. PMC4940894. PMID 26982003. S2CID 17842329.

- ^ Young, John J.; Tabin, Clifford J. (September 2017). "Saunders'southward framework for agreement limb development equally a platform for investigating limb evolution". Developmental Biological science. 429 (two): 401–408. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2016.xi.005. PMC5426996. PMID 27840200.

- ^ Scientists Find Chickens Retain Ancient Ability to Grow Teeth Archived June 20, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Ammu Kannampilly, ABC News, Feb 27, 2006. Retrieved October one, 2007.

- ^ International Chicken Genome Sequencing Consortium (9 December 2004). "Sequence and comparative analysis of the chicken genome provide unique perspectives on vertebrate evolution". Nature. 432 (7018): 695–716. Bibcode:2004Natur.432..695C. doi:10.1038/nature03154. PMID 15592404.

- ^ Warren, Wesley C.; Hillier, LaDeana W.; Tomlinson, Chad; Minx, Patrick; Kremitzki, Milinn; Graves, Tina; Markovic, Chris; Bouk, Nathan; Pruitt, Kim D.; Thibaud-Nissen, Francoise; Schneider, Valerie; Mansour, Tamer A.; Dark-brown, C. Titus; Zimin, Aleksey; Hawken, Rachel; Abrahamsen, Mitch; Pyrkosz, Alexis B.; Morisson, Mireille; Fillon, Valerie; Vignal, Alain; Grub, William; Howe, Kerstin; Fulton, Janet E.; Miller, Marcia M.; Lovell, Peter; Mello, Claudio V.; Wirthlin, Morgan; Mason, Andrew S.; Kuo, Richard; Burt, David West.; Dodgson, Jerry B.; Cheng, Hans H. (January 2017). "A New Chicken Genome Assembly Provides Insight into Avian Genome Structure". G3. 7 (1): 109–117. doi:10.1534/g3.116.035923. PMC5217101. PMID 27852011.

- ^ Gou, Xiao; Li, Ning; Lian, Linsheng; Yan, Dawei; Zhang, Hao; Wei, Zhehui; Wu, Changxin (June 2007). "Hypoxic adaptations of hemoglobin in Tibetan chick embryo: High oxygen-analogousness mutation and selective expression". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Office B: Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 147 (2): 147–155. doi:ten.1016/j.cbpb.2006.eleven.031. PMID 17360214.

- ^ Zhang, H.; Wang, X.T.; Chamba, Y.; Ling, Y.; Wu, C.X. (October 2008). "Influences of Hypoxia on Hatching Functioning in Chickens with Different Genetic Adaptation to High Altitude". Poultry Scientific discipline. 87 (10): 2112–2116. doi:ten.3382/ps.2008-00122. ISSN 0032-5791. PMID 18809874.

- ^ Nakane, Yusuke; Yoshimura, Takashi (2019-02-15). "Photoperiodic Regulation of Reproduction in Vertebrates". Annual Review of Creature Biosciences. Almanac Reviews. 7 (ane): 173–194. doi:10.1146/annurev-brute-020518-115216. ISSN 2165-8102. PMID 30332291. S2CID 52984435.

- ^ Brownlie, Robert; Allan, Brenda (2010-09-01). "Avian toll-like receptors". Prison cell and Tissue Research. Springer. 343 (1): 121–130. doi:10.1007/s00441-010-1026-0. ISSN 0302-766X. PMID 20809414. S2CID 2877905.

- ^ Pennisi, Elizabeth (24 May 2018). "Quaillike creatures were the but birds to survive the dinosaur-killing asteroid impact". Science. doi:10.1126/scientific discipline.aau2802.

- ^ a b Wong, Yard. One thousand.; Liu, B.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Ten.; Zhang, Z.; Meng, Q.; Zhou, J.; Li, D.; Zhang, J.; Ni, P.; Li, Due south.; Ran, L.; Li, H.; Zhang, J.; Li, R.; Li, S.; Zheng, H.; Lin, W.; Li, G.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Westward.; Li, J.; Ye, C.; Dai, Grand.; Ruan, J.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Y.; He, 10.; et al. (nine Dec 2004). "A genetic variation map for chicken with two.eight million unmarried nucleotide polymorphisms". Nature. 432 (7018): 717–722. Bibcode:2004Natur.432..717B. doi:10.1038/nature03156. PMC2263125. PMID 15592405.

- ^ a b c d Lawal, Raman Akinyanju; Martin, Simon H.; Vanmechelen, Koen; Vereijken, Addie; Silva, Pradeepa; Al-Atiyat, Raed Mahmoud; Aljumaah, Riyadh Salah; Mwacharo, Joram M.; Wu, Dong-Dong; Zhang, Ya-Ping; Hocking, Paul G.; Smith, Jacqueline; Wragg, David; Hanotte, Olivier (December 2020). "The wild species genome ancestry of domestic chickens". BMC Biology. 18 (1): 13. doi:ten.1186/s12915-020-0738-one. PMC7014787. PMID 32050971.

- ^

- ^ Fumihito, A; Miyake, T; Sumi, S; Takada, Thou; Ohno, S; Kondo, Due north (December 20, 1994), "One subspecies of the red junglefowl (Gallus gallus gallus) suffices every bit the matriarchic antecedent of all domestic breeds", PNAS, 91 (26): 12505–12509, Bibcode:1994PNAS...9112505F, doi:10.1073/pnas.91.26.12505, PMC45467, PMID 7809067

- ^ King, Rick (February 24, 2009), "Rat Set on", NOVA and National Geographic Boob tube, archived from the original on August 23, 2017, retrieved August 25, 2017

- ^ King, Rick (February ane, 2009), "Plant vs. Predator", NOVA, archived from the original on August 21, 2017, retrieved August 25, 2017

- ^ West, B.; Zhou, B.X. (1988). "Did chickens go north? New evidence for domestication". J. Archaeol. Sci. 14 (5): 515–533. doi:10.1016/0305-4403(88)90080-5.

- ^ Al-Nasser, A.; Al-Khalaifa, H.; Al-Saffar, A.; Khalil, F.; Albahouh, Chiliad.; Ragheb, G.; Al-Haddad, A.; Mashaly, M. (1 June 2007). "Overview of chicken taxonomy and domestication". World'southward Poultry Scientific discipline Journal. 63 (2): 285–300. doi:x.1017/S004393390700147X. S2CID 86734013.

- ^ Wang, Ming-Shan; et al. (2020). "863 genomes reveal the origin and domestication of craven". Cell Inquiry. thirty (eight): 693–701. doi:10.1038/s41422-020-0349-y. PMC7395088. PMID 32581344. S2CID 220050312.

- ^ Liu, Yi-Ping; Wu, Gui-Sheng; Yao, Yong-Gang; Miao, Yong-Wang; Luikart, Gordon; Baig, Mumtaz; Beja-Pereira, Albano; Ding, Zhao-Li; Palanichamy, Malliya Gounder; Zhang, Ya-Ping (January 2006). "Multiple maternal origins of chickens: Out of the Asian jungles". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 38 (i): 12–19. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2005.09.014. PMID 16275023.

- ^ Zeder, Melinda A.; Emshwiller, Eve; Smith, Bruce D.; Bradley, Daniel G. (March 2006). "Documenting domestication: the intersection of genetics and archaeology". Trends in Genetics. 22 (3): 139–155. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2006.01.007. PMID 16458995.

- ^ a b c d e CHOF : The Cambridge History of Food, 2000, Cambridge University Press, vol.i, pp496-499

- ^ Perry-Gal, L.; Erlich, A.; Gilboa, A.; Bar-Oz, G. (2015). "Earliest economic exploitation of chicken outside East asia: Bear witness from the Hellenistic Southern Levant". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the U.s.a. of America. 112 (32): 9849–9854. Bibcode:2015PNAS..112.9849P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1504236112. PMC4538678. PMID 26195775.

- ^ Brown, Marley (Sep–Oct 2017). "Fast Food". Archæology. 70 (5): 18. ISSN 0003-8113. Retrieved July 25, 2019.

- ^ Borrell, Brendan (1 June 2007). "Deoxyribonucleic acid reveals how the chicken crossed the sea". Nature. 447 (7145): 620–621. Bibcode:2007Natur.447R.620B. doi:10.1038/447620b. PMID 17554271. S2CID 4418786.

- ^ Storey, A. A.; Ramirez, J. M.; Quiroz, D.; Burley, D. 5.; Addison, D. J.; Walter, R.; Anderson, A. J.; Hunt, T. L.; Athens, J. S.; Huynen, L.; Matisoo-Smith, E. A. (nineteen June 2007). "Radiocarbon and DNA evidence for a pre-Columbian introduction of Polynesian chickens to Republic of chile". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (25): 10335–10339. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10410335S. doi:ten.1073/pnas.0703993104. PMC1965514. PMID 17556540.

- ^ Wilford, John Noble (5 June 2007). "Get-go Chickens in Americas Were Brought From Polynesia". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2007-06-07.

- ^ Gongora, Jaime; Rawlence, Nicolas J.; Mobegi, Victor A.; Jianlin, Han; Alcalde, Jose A.; Matus, Jose T.; Hanotte, Olivier; Moran, Chris; Austin, J.; Ulm, Sean; Anderson, Atholl; Larson, Greger; Cooper, Alan (2008). "Indo-European and Asian origins for Chilean and Pacific chickens revealed by mtDNA". PNAS. 105 (xxx): 10308–10313. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10510308G. doi:10.1073/pnas.0801991105. PMC2492461. PMID 18663216.

- ^ Thomson, Vicki A.; Lebrasseur, Ophélie; Austin, Jeremy J.; Hunt, Terry L.; Burney, David A.; Denham, Tim; Rawlence, Nicolas J.; Wood, Jamie R.; Gongora, Jaime; Girdland Flink, Linus; Linderholm, Anna; Dobney, Keith; Larson, Greger; Cooper, Alan (1 Apr 2014). "Using aboriginal Deoxyribonucleic acid to report the origins and dispersal of bequeathed Polynesian chickens across the Pacific". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (thirteen): 4826–4831. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111.4826T. doi:10.1073/pnas.1320412111. PMC3977275. PMID 24639505.

- ^ Jones, E.K.One thousand.; Prescott, N.B. (2000). "Visual cues used in the selection of mate by fowl and their potential importance for the breeder industry". Earth'south Poultry Science Journal. 56 (2): 127–138. doi:x.1079/WPS20000010. S2CID 86481908.

- ^ "About chickens | Compassion in World Farming". Ciwf.org.great britain. Archived from the original on April 26, 2017. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- ^ Fereira, John. "Poultry Slaughter Annual Summary". usda.mannlib.cornell.edu. Archived from the original on Apr 26, 2017. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- ^ Fereira, John. "Chickens and Eggs Annual Summary". usda.mannlib.cornell.edu. Archived from the original on April 26, 2017. Retrieved Apr 25, 2017.

- ^ "Towards Happier Meals In A Globalized World". World Watch Institute. Archived from the original on May 29, 2014. Retrieved May 29, 2014.

- ^ Ilea, Ramona Cristina (April 2009). "Intensive Livestock Farming: Global Trends, Increased Environmental Concerns, and Ethical Solutions". Journal of Agricultural and Ecology Ethics. 22 (2): 153–167. doi:x.1007/s10806-008-9136-3. S2CID 154306257.

- ^ Tilman, David; Cassman, Kenneth G.; Matson, Pamela A.; Naylor, Rosamond; Polasky, Stephen (Baronial 2002). "Agricultural sustainability and intensive product practices". Nature. 418 (6898): 671–677. Bibcode:2002Natur.418..671T. doi:10.1038/nature01014. PMID 12167873. S2CID 3016610.

- ^ "Broiler Chickens Fact Sheet // Animals Australia". Animalsaustralia.org. Archived from the original on July 12, 2010. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- ^ "UK Egg Industry Data | Official Egg Info". Egginfo.co.united kingdom. Archived from the original on December 30, 2016. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- ^ Glenday, Craig (April 26, 2011). Guinness World Records 2011. Mass Market place Paperback. p. 286. ISBN978-0440423102.

- ^ a b Browne, Anthony (March 10, 2002). "X weeks to live". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on May 16, 2008. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- ^ Patwardhan, D.; Male monarch, A. (2011). "Review: feed withdrawal and non feed withdrawal moult". Globe's Poultry Scientific discipline Periodical. 67 (ii): 253–268. doi:10.1017/s0043933911000286. S2CID 88353703.

- ^ Webster, A.B. (2003). "Physiology and behavior of the hen during induced moult". Poultry Science. 82 (6): 992–1002. doi:10.1093/ps/82.6.992. PMID 12817455.

- ^ Molino, A.B.; Garcia, E.A.; Berto, D.A.; Pelícia, M.; Silva, A.P.; Vercese, F. (2009). "The Furnishings of Alternative Forced-Molting Methods on The Performance and Egg Quality of Commercial Layers". Brazilian Journal of Poultry Science. eleven (two): 109–113. doi:ten.1590/s1516-635x2009000200006.

- ^ Yousaf, M.; Chaudhry, A.South. (1 March 2008). "History, changing scenarios and future strategies to induce moulting in laying hens" (PDF). World's Poultry Science Journal. 64 (one): 65–75. doi:10.1017/s0043933907001729. S2CID 34761543.

- ^ Fly, Colin (July 27, 2007). "Some homeowners find chickens all the rage". Chicago Tribune. [ permanent dead link ]

- ^ Pollack-Fusi, Mindy (December xvi, 2004). "Cooped upward in suburbia". Boston Earth.

- ^ Kreilkamp, Ivan (25 November 2020). "How Caring for Backyard Chickens Stretched My Emotional Muscles". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2020-11-25.

- ^ Boone, Lisa (27 Baronial 2017). "Chickens will get a beloved pet — just like the family dog". Los Angeles Times . Retrieved 2019-04-03 .

- ^ Barras, Colin. "Despite what yous might think, chickens are non stupid". world wide web.bbc.com. Archived from the original on June 6, 2021. Retrieved 2020-09-06 .

- ^ United Poultry Concerns. "Providing a Skillful Home for Chickens". Archived from the original on June v, 2009. Retrieved May 4, 2009.

- ^ "Choosing Your Chickens". Clucks and Chooks. Archived from the original on July xxx, 2009.

- ^ gamecock – Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary – first use of word – 1646

- ^ "Should cockfighting be outlawed in Oklahoma?". CNN. 26 Nov 2002. Archived from the original on 19 June 2009. Retrieved 17 August 2009.

- ^ Sherman, David M. (2002). Tending Animals in the Global Village. Blackwell Publishing. 46. ISBN 0-683-18051-vii.

- ^ Joe G. Berry. "Artificial Incubation". Oklahoma Cooperative Extension Service, Oklahoma Country University. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 4, 2010. Retrieved September 29, 2010.

- ^ Phillip J. Clauer. "Incubating Eggs" (PDF). Virginia Cooperative Extension Service, Virginia State University. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 13, 2010. Retrieved October 1, 2010.

- ^ White, Tiffany M.; Gilden, Donald H.; Mahalingam, Ravi (October 2001). "An Animal Model of Varicella Virus Infection". Brain Pathology. eleven (4): 475–479. doi:ten.1111/j.1750-3639.2001.tb00416.x. PMC8098339. PMID 11556693. S2CID 26073177.

- ^ "Forget dogs and cats. The near pampered pets of the moment might be our backyard chickens". USA TODAY . Retrieved 2019-04-03 .

- ^ CDC (2019-03-xviii). "Keeping Backyard Poultry". Centers for Illness Control and Prevention . Retrieved 2019-04-03 .

- ^ "Overview of Omphalitis in Poultry". Merck Veterinary Manual. Archived from the original on January 13, 2017. Retrieved Jan 10, 2017.

- ^ "Clucks and Chooks: guide to keeping chickens". Henkeeping.co.uk. Archived from the original on January fifteen, 2010. Retrieved Oct 26, 2009.

- ^ Meleisea, Malama (March 25, 2004). The Cambridge History of the Pacific Islanders. Cambridge Academy Press. p. 56. ISBN9780521003544. Archived from the original on September xiii, 2016. Retrieved March 13, 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ Crawford, Michael H. (March thirteen, 2019). Anthropological Genetics: Theory, Methods and Applications. Cambridge University Printing. p. 411. ISBN9780521546973. Archived from the original on September 13, 2016. Retrieved March 13, 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ Karayanis, Dean; Karayanis, Catherine (March 13, 2019). Regional Greek Cooking. Hippocrene Books. p. 176. ISBN9780781811460. Archived from the original on September thirteen, 2016. Retrieved March 13, 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ Chiffolo, Anthony F.; Hesse, Rayner Due west. (March 13, 2019). Cooking with the Bible: Biblical Nutrient, Feasts, and Lore. Greenwood Publishing Grouping. p. 207. ISBN9780313334108. Archived from the original on September xiii, 2016. Retrieved March 13, 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ Flenley, John; Bahn, Paul (May 29, 2003). The Enigmas of Easter Island. Oxford Academy Press, UK. p. half dozen. ISBN9780191587917. Archived from the original on September 13, 2016. Retrieved March thirteen, 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ Dash, Mike (July 23, 2012). "On the Trail of the Warsaw Basilisk". Smithsonian. Retrieved 2021-12-28 .

- ^ "Cockatrice". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2021-12-28 .

- ^ Budge, Ernest (1930). Amulets and Superstitions. Oxford University Press.

Further reading

- Greenish-Armytage, Stephen (October 2000). Extraordinary Chickens. Harry Due north. Abrams. ISBN978-0-8109-3343-ix.

- Smith, Folio; Charles Daniel (April 2000). The Chicken Book. University of Georgia Press. ISBN978-0-8203-2213-1.

- Andrew Lawler (2014). Why Did the Chicken Cantankerous the World?: The Epic Saga of the Bird that Powers Civilization. Atria Books. ISBN978-1-4767-2989-3.

External links

- Chickens at Curlie

- Video: Chick hatching from egg

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chicken

0 Response to "What Is the Time Period That a Chicken Takes to Lay Eggs Again"

Postar um comentário